Philosophy and Ethical Governance

My Journey With Philosophy

The issue that led me to philosophy was my acute discomfort with the suffering of many impoverished and marginalised people, especially children and old people (and subsequently animals), and the indifference of most of us to actually find a solution, or even to attempt temporary relief. Yet I was brought up in a family, like most others, where I was told that one must not give alms to beggars as they were lazy and did not want to work.

So, as I saw more of such suffering, and in India there is plenty, my mind started persistently asking why, and seeking answers about my own ethical standpoint towards this. How can we change this reality, and more urgently, what should I do to help this change.

My years as a student in college (1967-1972) were also the years of the growth of Naxalism in India. Our college was particularly affected with a significant group of students dropping out of college and joining the naxal movement in different parts of India. For a while the college walls were full of Naxal slogangs, and a few funny ones, like “Mein

Mao Tse Tung

aa gaya hoon”.I toyed fir a while with the idea of becoming a Naxalite and even read some of their literature and attended a few meetings, but it did not catch my imagination and I recognised that I had to understand the problem better before I can think of preventive and curative strategies.

The search of understanding such issues finally led me to turn to philosophy (and psychology), rather than politics and economics, as many others did.

As an MA student in philosophy, I soon became fascinated by epistemology and ethics. On completing my MA, in 1972, I was very fortunate to be offered a lectureship in philosophy at my old college.

For the next eight years I taught philosophy, initially at St. Stephen’s College, and subsequently at the North- Eastern Hill University, Shillong. My initial two years or so of teaching at my old college were ecstatic. I had a very bright group of students studying for their BA (Hons) and MA in Philosophy, and taught symbolic logic to the first year English and History honours students, who were also an exceedingly bright lot. I was concurrently the tutor of Allnut South residential block and lived in College, in the tutor’s rooms, where I hosted the weekly meeting of the philosophical society – or philosoc – as it was popularly known.

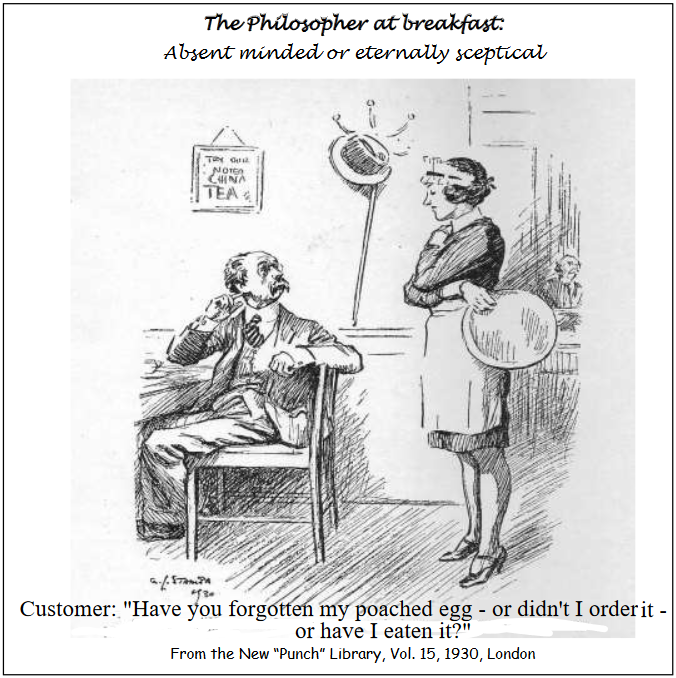

Towards the end of my MA I had begun to grasp that the essence of epistemology was the fundamental truth that nothing (at least nothing novel) could ever be known with certainty. From this it inevitably followed that all ethical “knowledge” was also subject to doubt, and one could never be certain about what was good or bad, or right or wrong.

To me this had a very liberating effect, for most of my life (which was then only 20 years) I had struggled to understand what was truly ethical, and why. But when, as a freshly liberated teacher, I bgan to share this sense of liberation with my students, sometimes using sophistry, convincingly arguing a point of view in one class and then convincingly arguing its opposite in the next. But I soon discovered that some of my more sensitive students were incapable of dealing with such eternal scepticism, and became very disturbed in one way or another. For the first time I began to how disastrous it was for some students, especially the more sensitive ones, to be exposed to a persuasive teacher who essentially planted endless doubts in their mind, without providing a method, or even the hope of a method, of escaping from this intellectual and emotional morass. This also made me realise why philosophy would never be a universally popular discipline, as certainty was an important prop, perhaps even a necessity, for a large proportion of people.

My next challenge came after a couple years of teaching. Right from the start I had a feeling that I was not adequately informed about the various problems of philosophy, but efforts to read and understand them were frustrated by a lack of enthusiasm, which I put down to laziness (always having had the tendency to laze rather than work hard). One day I was visiting my old teacher Bose Sahib, and in the middle of our conversation Bose Sahib told how, once, the philosopher Wittgenstein, who had the reputation of reading very little philosophy, asked Bose Sahib, on seeing his impressive collection of books, whether he actually read all these books. Whan Bose Sahib defensively replied that “You have to read these books in order to become aware of the problems of philosophy”, Wittgenstein reportedly exclaimed, “My dear fellow, if you don’t already have the problems of philosophy, why do you want to acquire them...”?

On my drive home, after talking to Bose Sahib, I suddenly realised what my problem was. I was not intellectually, temperamentally, or even emotionally, a philosopher.

My preoccupation with philosophy was focused around three undamental issues, and another few derivative ones. The fundamental issues that continue to intrigue me, even after 50 years of enquiry, relate to, first and foremost, the belief that we have no method of determining which, if any at all, of our perceptions, beliefs, conjectures, or even deductions, are true in the sense that they are certain and there is no possibility of error. And I despair, as there seems no hope of finding any certainty whatsoever through a study of philosophy.

The second major worry, which is a consequence of this first one, is the recognition that if we do not have access to certainty then we can’t really be certain that what we consider to be good or bad is actually so. This, in one swift sweep, removes the whole basis of ethics and morality.

Since childhood, I wondered about compassion, in myself for others, and among others for each other. For a long time I considered compassion to be unquestionably an essential part of individual ethics, even while I struggled to discover what else was certainly a part of any ethical system. But the newly discovered fact that nothing was known with certainty sent everything up in the air.

Added to these was our inability to establish the existence of a free will among human beings. Clearly, if we do not have a free will, then we cannot be held responsible for any of our actions or inactions. In some senses, if there is no free will, then all the philosophical queries described above become irrelevant for, even if we knew what was certain and what was not, what was good and what was bad, and what was the purpose of our lives and of the world, there was nothing we could do about these as our thoughts and actions were not in our control.

But we make judgements all the time, and we are judged all the time. More troublesome, we give advice to others and those of us who have had the privilege of becoming parents, were called upon to decide how to bring up our child, and how to determine what would be a good influence. But does it all matter? And who are we to determine all this? Are we not ourselves predetermined to choose whatever we do? So where do we start, or is there no beginning or end?

Also, if there is no free will, then what is the basis of the judicial system, which determines guilt and imposes punishment. If someone murders, do they have a choice? And if not, how can you punish them? But then, if you punish them, or applaud their punishment, do you have a choice in the matter or is that how you are conditioned to act and think?

My first few carefree years of studying and teaching philosophy not only brought me face to face with all these and other similar dilemmas but led me to significantly change my role as a teacher of philosophy (if one can ever “teach” philosophy). I adopted the personality of an intellectual schizophrenic: where one me , the all-doubting me, struggled with universally prevalent uncertainties, while another me arbitrarily accepted some truths – mainly because they were widely accepted – and proceeded to apply the philosophical method to these “acquired certainties”.

Lecturing on ethics to senior civil servants was very challenging. There was the constant danger of being dubbed a theoretician who had little or no understanding of real-life challenges and dilemmas. There was also the danger of appearing to preach, something that was not taken kindly to by the civil servants, who did not like being preached to by someone whom they rightly considered to be totally inexperienced in the sorts of challenges they faced.

It took some years to, gradually, and through trial and error, develop an approach that was constructive and acceptable to the bureaucrat- participants. Such an approach involved merging philosophical and psychological concepts and analysing real-life administrative challenges, many of which were shared , on the promise of anonymity, by the participants themselves.

Essentially three questions were discussed. First, what is right or ethical , as opposed to wrong or unethical? Much of the debate centred around exceptions and grey areas rather than absolute values – of course following laws and rules was right, but when is it better to violate a rule or law than to follow it? When there is a “bad” means leading to a good end, or a “good” means leading to a bad end, what should one do, and how does one decide?

Second, why should I be moral? Here the debate moved beyond religious and traditional moral dictums (God’s wrath, heaven and hell, or even pricking conscience) and focussed on cases where being ethical was prejudicial, or even dangerous, and certainly disadvantageous. There were also questions of how far one could go before it really became unethical!

Third, there was the theoretical question of how one can make the government/system more ethical - more conducive to and supportive of ethical behaviour?

Though much work was done in the 40 years or so since the initiation of ethics and administration courses and lectures, initially at the IIPA, and subsequently at many other institutions where civil servants came for training, much still needs to be thought out and written. This website is a start in that direction.

Shekhar Singh

To be uploaded:

1. Lectures on Ethics and Administration